**** Updated to add votes on the motion to vacate and race for Speaker ****

October began with a weekend of high drama in Congress. With a deadline of October 1 to prevent the fourth partial shutdown in a decade, both the Senate and the House have been working on bills to keep the government open but the prospects looked bleak until on Saturday when a bill rapidly passed through both Houses and was signed by President Joe Biden with scant hours to spare before the deadline. The bill extends funding and certain program authorizations through November 17., allowing more time to resolve differences.

The bill was a victory for pragmatic compromise after weeks of partisan wrangling, but what was actually agreed to and who voted for and against and why?

The shutdown challenge

The 1884 Antideficiency Act (amended in 1950) requires federal agencies to gain approval from Congress before spending any money. This approval takes the form of 12 annual appropriations bills, each setting out the funding for different areas of spending. In reality, Congress rarely manages to pass all of these bills. In the nearly 50 years since the current system was introduced in 1977, they've only managed to pass all the bills 4 times - 1977 (Carter), 1989 (Bush), 1995 (Clinton), and 1997 (Clinton). In 2023, Congress has yet to approve any of the 12 bills.

To avoid the funding coming to a halt in contentious areas, a partial shutdown, Congress can pass continuing resolutions as a stopgap measure. These measures keep government open but defer those spending decisions to a later date. Congress has disagreed over what should go into this year's short term stopgap measure, with Republicans wanting increased spending on border security and Democrats keen to maintain funding support for the war in Ukraine.

Let's take a look at the bills which have brought us to the current situation, starting back in the spring.

The debt ceiling bill

In June 2023 Congress passed and President Biden signed the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 which raised the federal debt ceiling and set spending limits in each of fiscal years 2024 (which begins October 2023) and 2025. The bill received broad bipartisan support, passing with a 63% margin in the Democrat controlled Senate and 72% in the Republican controlled House. This chart illustrates the voting breakdown by party, showing that there was a reasonable spread of supporters and dissenters in both parties.

House vote

Senate vote

One interesting feature of the the Act is that it requires Congress to approve funding for the government before January 1, otherwise limits for defense spending will be slashed by just over 4% ($36bn) while non defense spending would increase by about 5% ($33bn). This measure was designed to incentivize Congress to enact full year legislation rather than relying on continuing resolutions.

The appropriations bills

Raising the debt ceiling should have paved the way for smooth passage of the 12 appropriations bills this year. Unfortunately, that was not the case. This stakeholder page shows the current situation. 12 bills have been introduced by the Senate and 10 by the House. Only one of these bills, "The Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act," has been approved by the House; it has not yet been passed by the Senate. The House vote on the bill split almost entirely along party lines, 219 yes to 211 no, with Republicans supportive and Democrats opposed. None of the appropriations bills have yet been signed into law. There are a number of reasons for the logjam: measures to block the abortion pill mifepristone from being dispensed at pharmacies in the Agriculture bill was opposed by moderates for example, and inclusion of money for Ukraine has proven to be a stumbling block, as well as Republican demands for more money for border security.

The continuing resolutions

With time running out, both chambers introduced continuing motions to give themselves more time to resolve differences. The Senate attached their legislation to an existing FAA reauthorization bill. The compromise bill included $6.12 billion in total aid for Ukraine (less than the $24 billion sought by the White House) as well as additional border security funding. While the bill passed procedural votes in the Senate and was poised to cross over, some House Republicans signalled that they would not support any bill with Ukraine funding.

The House, meanwhile, struggled to identify a suitable compromise which could attract the necessary votes until House Speaker Kevin McCarthy introduced HR5860 on Saturday night. This bill did not include funding for Ukraine or funding for additional border security and therefore managed to attract sufficient votes from both parties to pass the House 335 - 91. The new bill then swiftly passed through the Senate with broad support, passing 88-9. President Biden signed the bill with hours to spare, though warning that support for Ukraine cannot be interrupted.

This scorecard shows how the legislators voted.

Senate voting on HR5860

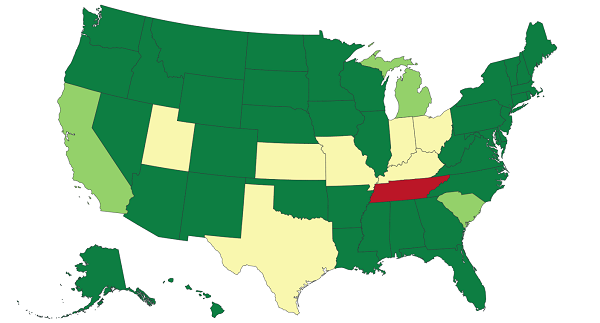

The map below show Senate voting distribution by state. Green indicates both senators votes yes, light green means only one senator voted and voted yes, yellow means the senators split (one yes one no) and red is both senators voted no. Click the map for more details:

All Democrat Senators voted in favour, and only 9 Republicans voted against. Here are the dissenters:

House voting on HR5860

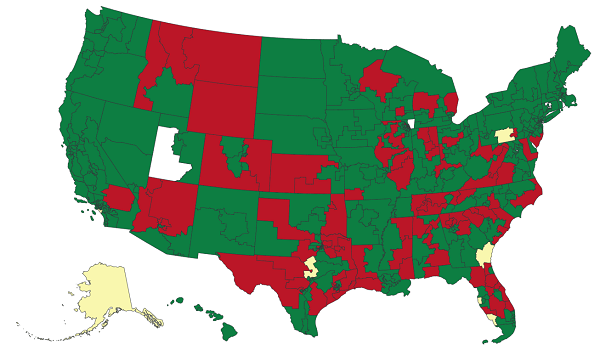

This map shows the House vote by district. Green means that representative voted yes, red means no, yellow means no vote, and the white district in Utah is currently vacant. Again, click for more details.

Voting in the House was more mixed, with 126 Republicans joining Democrats in voting in favor, ensuring its passage. Only 1 Democrat voted against - Rep. Mike Quigley from Illinois, who is the co-chair of the Congressional Ukraine Caucus, voted against the legislation to protest the lack of funding for Ukraine. 91 Republicans voted against; you can see the list by clicking the map above.

What happens next?

Shutdown has been averted for now, but only until November 17. Congress has until then to resolve differences , particularly continuing funding to support Ukraine and on border security. This week both chambers will begin that task so expect yet more standalone bills, some omnibus bills combining different measures, and yet more shenanigans. If they cannot come to agreement, there may be more continuing resolutions -- but remember the January 1 deadline, with those automatic cuts to defense, is hanging over the whole process.

The big winner of course is Fat Bear Week, which was facing cancelation this year if the National Parks Service was forced to shut down. The good news is that the annual competition can now proceed, so get voting for your favourite and fattest bears starting on October 4.

courtesy of Carol M. Highsmith, originally published on Rawpixel

The Republican response

The actions of the House Speaker to pass the spending deal incensed certain Republicans, who were opposed to any compromise with the Democrats regarding border security. They were led by hard-line conservative Rep. Matt Gaetz from Florida. On Monday, Gaetz introduced a 'motion to vacate' to remove McCarthy from office.

The motion to vacate

A motion to vacate is a rarely used procedural device. The Constitution did not specify procedures for managing the House of Representatives, in fact the only mention of the role of Speaker in the entire Constitution is: "The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker,". So it was up to the House to decide how the "chusing" should take place. "Jefferson's Manual", adopted in 1837 as a procedural guide, helpfully states that: "A Speaker may be removed at the will of the House" but it was left to Speaker Joseph Cannon in 1910 to determine how that will should be expressed. In a speech, when facing a revolt in his party, he declared that he only had two options left to him: resign or "declare a vacancy in the office of Speaker." By offering to oust himself he forced a vote to put his detractors on the record, which he won overwhelmingly.

The motion has only been filed one more time since 1910. In 2015 Rep. Mark Meadows filed a motion to vacate the speakership of Rep. John Boehner. While this contributed to his decision to resign later that year, it was never actually put to a vote.

So, no motions to vacate have ever been successful, and there has only been one such vote in the history of the House. Matt Gaetz's move to remove McCarthy therefore, while not unprecedented, was bold and very unusual. But not entirely unexpected. To understand why, we need to look back in time.

From 1910 to 2019 the threshold for bringing a motion to vacate remained at one member. In 2019, the Democrat-controlled House modified the rule to allow the resolution to be brought only "if offered by direction of a party caucus or conference", thereby making it much more difficult to challenge an incumbent Speaker. In January, however, McCarthy was forced to make a number of concessions to secure the backing of rebellious Republicans, one of which was returning the threshold to just a single member. The hard-line republicans, led by Matt Gaetz, were clearly signalling that they would act to remove McCarthy if he failed to meet their expectations. And act they did.

The votes

The motion to vacate involved two votes. The first was a move to 'table the motion', which if successful would kill the motion. So those in favor of removing McCarthy needed to vote against the move. After some soul-searching, Democrats decided they couldn't support McCarthy and therefore united to all vote against. On this occasion, 11 Republicans chose to join them. Here's the vote breakdown:

And these are the Republican who voted against the move to kill the motion:

With the move to table the motion defeated, the House proceeded to vote on the motion to vacate itself. This time, rebellious Republicans needed to vote in favor to oust the Speaker. All Democrats voted to oust once again and just 8 Republicans opted to join them. This was enough, however, to overturn the Republican's slim majority in the House by 212 votes to 210 and give Speaker McCarthy the dubious honor of being the first Speaker in US history to be removed from his post. Here's the vote breakdown:

And again, here are the Republicans who voted to remove the Speaker:

It's worth noting a few things about how the vote broke down:

Representatives Warren Davidson (Ohio), Cory Mills (Florida) and Victoria Spartz (Indiana) voted against tabling the motion but also against removing the Speaker. Presumably they felt that while they supported the Speaker themselves, the House should be given the opportunity to vote on the matter.

While most of the 8 Republicans who voted to oust were well known hard-line conservatives, there were audible gasps of surprise when Rep. Nancy Mace (South Carolina) chose to join them. Mace and McCarthy had sometimes disagreed and Mace told the "The View" shortly before the vote that McCarthy had promised her things which never materialized and that she empathized with the frustrations of Matt Gaetz, but no one expected Mace to vote against him and it has triggered anger within the party.

Five Democrats did not vote on the move to table - Cori Bush (Missouri), Frederica Wilson (Florida), Nancy Pelosi (California), Mary Peltola (Alaska) and Emilia Sykes (Ohio). And two Republicans - John Carter (Texas) and Anna Luna (Florida). But it was slightly different on the vote to vacate itself. Only four Democrats did not vote - Bush, Pelosi , Pelotola and Sykes. And this time there were three Republican non voters - Carter, Luna and Lance Gooden (Texas).

And, because we love a good map, here's the breakdown by district of both votes. Green means the representative voted against ousting McCarthy, red means they voted in favor, yellow means no vote and the white district in Utah is currently vacant. Click to see more details.

What happened next?

Kevin McCarthy announced shortly after the vote that he would not run for the speakership again. The battle to succeed him began, with Majority Leader Steve Scalise (Louisiana) and House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan (Ohio) as frontrunners. First up was Scalise, who spent a week trying to garner the necessary support before pulling out without a vote on the floor. So the baton passed to Jim Jordan to try to get enough Republican votes to give him a majority in the House.

Read this blog post to learn more about Jim Jordan's legislative record and his (doomed) run for the Speaker. And this post for an analysis of the new candidates.

About BillTrack50 – BillTrack50 offers free tools for citizens to easily research legislators and bills across all 50 states and Congress. BillTrack50 also offers professional tools to help organizations with ongoing legislative and regulatory tracking, as well as easy ways to share information both internally and with the public.