By: Sarah Johnson

This week we’ll take a deeper dive into two very popular bills, the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act of 2017 and the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act of 2019. These bills share similar methods aimed at accomplishing a common goal. Let’s take a look at the history and facts behind the main issue these bills work to address and look at what changed in the 2019 version.

How Did We Get Here?

As I am sure we are all aware, immigration policy in the United States is a bit of a mess. From what we see in the news to what we experience in our day to day lives, many modern aspects of immigration aren’t dealt with adequately with our current policy. One such aspect of immigration policy which has a dramatic effect on the US economy is the process by which people who live and work here on visas are awarded green cards. Herein lies the problem both Fairness for Highly-Skilled Immigrant Acts work to address.

Visas

Green cards, or permanent residency cards, are awarded to people to allow them to stay in the United States and work (semi) permanently. Many different kinds of green cards are given out each year ranging from ones given through family, employment, refugee or asylee status, human trafficking and crime victims, victims of abuse and other categories. Once someone has their green card, it is valid for ten years. Green cards can be revoked if the person commits a crime.

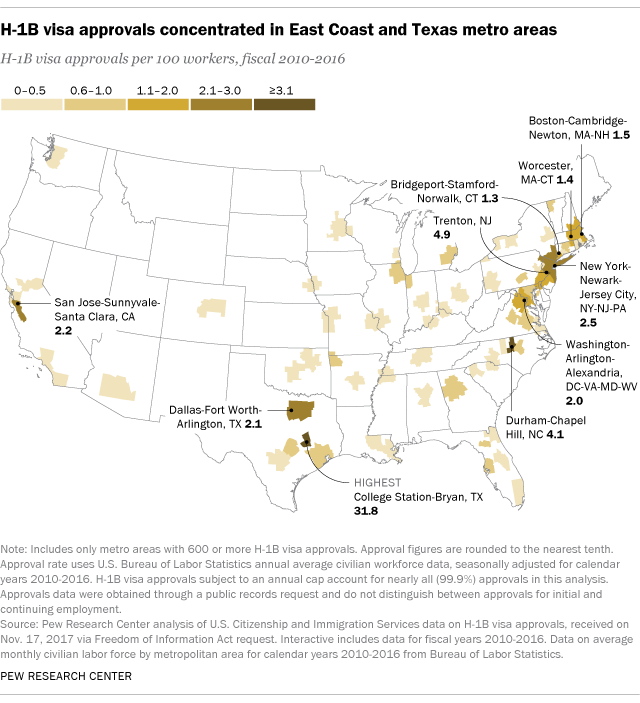

There are three different visas for employment-based green cards we should be familiar with to understand the issue. First, familiar to most of us, H-1B visas. The H-1B program allows US companies to temporarily employ foreign workers for jobs that require the “application of highly specialized knowledge and a bachelor’s degree or higher in the specific specialty, or its equivalent”. H-1B specialty fields cover industries like science, engineering, coding, information technology, teaching or accounting. The top companies who hire people with H-1B visas are: Cognizant, Amazon, Microsoft, IBM, Intel and Google. Here is a great graph from Pew Research showing where most H-1B visa holders live.

Second, are the EB-2 and EB-3 visas.

EB-2 is an Employment Based Second Preference visa. People are eligible for this visa if they have an advanced degree or its equivalent, or if they are a foreign national who has “exceptional ability”. People hoping to obtain one of these visas need an official academic record proving their degree, documentation of at least 10 years in their occupation and other items like proof of salary, recognition of achievement or membership to special organizations.

EB-3 is an Employment Based Third Preference visa. To qualify for this visa, people need to be either skilled workers, professionals or other workers. “Skilled workers” are people whose job requires a minimum of 2 years training or work experience and are not jobs temporary or seasonal in nature. “Professionals” are people whose job requires at least a U.S. baccalaureate degree or a foreign equivalent and have a job within that profession. The “other workers” subcategory is for people performing unskilled labor requiring less than 2 years training or experience, but still are not jobs temporary or seasonal in nature.

Green Cards

All of the following numbers are based on green cards issued in 2016. The US issued almost 1.2 million green cards in 2016. The majority of the green cards, close to 70%, ~800,000 green cards, were awarded to people immigrants who had family members already in the United States. In contrast, only about 140,000, or less than 12%, of the green cards were awarded to immigrants related to employment. Further, more than half of those 140,000 employment-based green cards were given to the spouses and children of primary applicants.

The United States has a policy stating no country can be awarded more than 7% of the combined total number of visas allowed to family and employment-based preferences. Doing the math on the 140,000 employment based green cards given out, a 7% cap means only around 9,800 green cards can go to immigrants from a particular nation each year.

A huge side-effect of the country cap is systemic bias toward smaller countries with fewer people immigrating to the US and a huge bottleneck for large population countries like India and China. India currently has over 300,000 people and China has over 65,000 people in line for green cards. More people from India come to the US on high-skilled work visas (H-1B or EB-2 visas) than any other country. There are between 700,000 and 2 million immigrants currently in the states from India. With the cap at 9,800 people per year, it would a least take 71 years (for 700,000 people) and at most take 204 years (for all 2 million) for everyone to obtain a green card. In contrast, people who immigrate from smaller nations could get a green card in just a few years.

Why is this a Problem?

H-1B visas are meant to have “dual intent”. Dual intent means people with these visas can work in the US but also apply for green cards at the same time. This dual intent policy was intended to allow these workers a chance to make the decision of whether they intend to return home or remain in the states for longer. In practice, though, it actually serves to put less pressure on the company or country to provide green cards to the holders of these visas since they are already here and working.

The failure of the dual intent policy leads to two major problems: uncertainty in status impacting visa holder’s ability to plan and live their lives and a resulting impact on the talent available in the United States. If people from highly skilled countries do not think it is attainable for them to obtain permanent legal status in the United States, they could well choose to start their lives over in a different country, like Canada.

People also may not choose to come to the States because people with H-1B visas cannot switch jobs as it impacts their place in line for green cards. Green card applications are attached to job titles, so people with these visas are unable to accept a promotion without starting the process over. This further leads to issues with companies hiring people on a H-1B visa at an entry level salary and never promoting them or giving them a raise because they do not have another option. Where people with legal status would accrue time and experience leading to promotions and raises as incentives to stay, H-1B holders can be ignored and exploited.

The final main issue effecting H-1B visa holders is children “aging out” and having to return to a country they have never known. (Does this issue sound familiar? It is similar to the issue with DACA, more on that here). H-B1 spouses and dependent children under 21 are allowed to join the visa holder. Depending on how long the visa holders must wait to be awarded a green card, their child could turn 21 and be forced to return to their country of origin unless they can obtain their own H-1B visa.

What is the 2017 Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrant Act?

The first Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrant Act, S281, attempted to address this visa/green card backlog issue. This legislation would have primarily done two things:

- Remove the cap for employment-based visa. This bill would change the issuing system to a first-come, first-serve system. The thought behind this is it gives all immigrants an equal chance to obtain a green card by awarding permanent residency by application date and no longer taking country of origin into account.

- Increase the cap per-country for employment-based and family-based preference category visas from 7 percent to 15 percent. This would allow families to reunite more quickly.

If this had been implemented, it would have significantly reduced the backlogs that countries with large populations have been experiencing. This would address issues with visa holders not being able to progress with their careers along with reducing the probability of their children “aging out” and getting sent back to their countries of origin.

What is the 2019 Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrant Act?

After the first Act failed, a second one was introduced in the beginning of 2019. HR1044 / S386 was introduced at the beginning of February 2019. These bills follow a lot of the same ideas as the 2017 Act, and would:

- Outline a transition period to eliminate the per-country limit for employment-based immigrants.

- In FY 2020, 15% of the immigrant visas in EB-2, EB-3 and EB-5 are reserved for beneficiaries from countries that are “not one of the two states with the largest aggregate numbers of natives who beneficiaries of approved petitions” in those categories (ie. China and India).

- FY 2021 and FY 2010 drop the limit to 10%.

- Without adding any new green cards, it would increase the per-country caps for family-sponsored green cards from 7 percent to 15 percent.

- The bill outlines primary beneficiaries for this, focusing on cases for Mexican and Filipino siblings and married sons and daughters of US citizens with priority dates (dates when the sponsors applied) between 1995 and 1998.

- S386 additionally creates a “first-come, first-served” system to help alleviate the backlogs and allow green cards to be awarded more efficiently.

This new version of the Act attempts to address many of the problems or concerns with the first bill. It has a transition period to ensure that not all visas go to the two countries waiting for the most (India and China). The new version also includes a provision stating no one who is the beneficiary of an employment-based immigrant visa approved before the bill’s enactment will receive a visa later than if the bill had never been enacted. In other words, they will not have their visa taken away so it can be awarded to someone else based on the “first come, first served” enactment.

When speaking about the report, Senator Mike Lee (the primary sponsor of the Senate version of the bill), stated

“Immigrants should not be penalized due to their country of origin. Treating people fairly and equally is part of our founding creed and the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act reflects that belief. Immigration is often a contentious issue, but we should not delay progress in areas where there is bipartisan consensus just because we have differences in a other areas.”

Conclusion.

After researching this topic, I definitely think a bill like this is warranted and should be more central to our immigration policy debate. It seems like a fairly easy problem to address from both sides of the aisle because there are many positive impacts for both sides to feel good about. The current cap does not appear to serve an economic purpose, if anything it negatively impacts our economy (disincentivizing talent). The backlog is severe and we need to figure out a better process for intelligent people who want permanent residency. By improving this process, we will be better able attract skilled talent which will in turn make the US more competitive in the global market. Finally, it will unite families who have been separated for years.

There are also some issues I can see with eliminating the cap. It could increase the number of people who try to immigrate to the states because they think it will be easier, which would effectively make these changes moot. I could also see future issues being raised from smaller countries having to wait exorbitant amounts of time compared to what they’re used to due to the massive influx of eligible people from high population countries.

I’m not sure there is a perfect solution to this problem since the balance of issues is always changing, but this bill does seem to take steps that make a lot of sense for where we stand today.

Cover Photo by Nitish Meena on Unsplash

About BillTrack50 – BillTrack50 offers free tools for citizens to easily research legislators and bills across all 50 states and Congress. BillTrack50 also offers professional tools to help organizations with ongoing legislative and regulatory tracking, as well as easy ways to share information both internally and with the public.