Thanks to a tweet from @VerifiedVoting I watched this video about Colorado’s risk-limiting audits this year and have become obsessed with learning all I can about it.

“Confidence in the elections process… is the basis of the democratic republic in which we live”

Watch Colorado’s Risk-Limiting-Audits in action, a pioneering step in election security & voter confidence nationwide #VerifyOurVote @COSecofState #COpolitics https://t.co/K9d2Py3RMU— Verified Voting (@VerifiedVoting) June 5, 2018

In case you can’t see the tweet, here’s the link to the video “Colorado’s risk-limiting audit” published by the Colorado Secretary of State (video also embedded at the end of this post): https://youtu.be/1flC9NQv51g — which I’m very disappointed to see has been removed by the user, but maybe it will come back. Luckily the Arapahoe County Clerk still has their video about implementing their Risk-Limiting Audit here.

My favorite quote from the (removed) video is:

“Election outcomes should be verified and can be verified; that can happen.” — Mark Lindeman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science, Columbia University

I must agree. In light of concerns about Russia’s intention and ability to tamper with our 2018 midterm election, safeguarding our elections is more important than ever. Risk-limiting audits are being proposed as an excellent tool for verifying that the results reported do in fact match the will of the people. Let’s take a look at how risk-limiting audits work in theory, how they got to be a thing in Colorado, how the process has unfolded so far, and maybe take a peek into the future

Risk Limiting-Audits — The Basic Idea

The idea of auditing an election after it happened makes me think of the most famous recount in my lifetime, the 2000 presidential election which brought us “hanging chads”, “butterfly ballots”, and President George W Bush.

It turns out the 2000 presidential election result got lots of people thinking about how to best make sure the reported result of an election reflects the actual votes cast. Quoting from the fantastic paper “Implementing Risk-Limiting Post-Election Audits in California” from 2009:

Nearly a decade after the 2000 presidential election fiasco, the “paper trail debate” has all but ended: More and more jurisdictions recognize that without indelible, independent ballot records that reliably capture voter intent, auditing election outcomes is impossible. As auditable voting systems are adopted more widely, election researchers are studying how to audit elections efficiently in a way that ensures the accuracy of the electoral outcome. The literature on the theory and practice of election auditing has exploded recently: There have been nearly 70 papers and technical reports since 2003

Audits can be thought of as “smart recounts”: Ideally, they ensure accuracy the same way recounts do, but with less work. Moreover, audits can check the results of many contests at a time, not just one contest on each ballot. And audits can take place during the canvass period, before an incorrect outcome is certified. Audits help check the integrity of voting systems that use computerized or electromechanical vote recording and tabulation equipment.

As more and more jurisdictions get on board with the idea of post-election audits, it makes sense to figure out best practices for auditing an election. Auditing may seem like a completely straightforward process on first consideration. Check 1% or 10% of the ballots, make sure they are “valid”, bada bing, bob’s your uncle. In reality, there’s a whole lot of nuance involved in auditing an election, some of which is quite interesting and fun to think about. Hence the 70 papers mentioned above (and many many since).

The fundamental idea of a risk-limiting audit features a dramatic shift away from the above straight-forward audit game plan of simply looking for errors. Many modern voting technologies, like optical scanners, will inevitably produce some errors; that means we have to think about the risk that the election result reported by the machines is wrong.

If our audit detects an error, and it probably will, what do we do? Feel bad? Keep auditing? Decide to do a full recount? What if the margin of victory was huge and the error rate in the audit is low? Or vice versa? If we find an error what do we do?!??

This is where risk-limiting audits come in. Our goal with a post-election audit isn’t the same as the goal of a financial audit, where you want to ferret out every error; we just want to make sure our election result accurately reflects the person the voters actually picked. That means we can look at the problem from the other way around. Instead of just auditing a set percentage of ballots and tallying up errors, we can design our audit to keep looking at additional ballots until we have adequately convincing evidence that the reported winner actually won — and then we are done. If you’ve reported the result of an election incorrectly, you’ll likely never reach the requisite level of certainty that the results were correct, which means you will continue counting ballots until you’ve done an entire manual recount and overturned the result.

The level of certainty you decide you need to stop auditing is the level of risk. In other words, the risk being limited isn’t that the result is wrong, but rather is the risk you fail to overturn a wrong result. Spoiler alert: this shift in point of view from looking for errors to confirming the result lets you get more certain results with less work (often much less work). Because math!

Risk-Limiting Audits — Exciting Math Explanation (!!)

Now you are hopefully as excited as I was to learn how risk-limiting audits work. A great place to start learning about both the mathematical and practical issues at play is in the Colorado Risk-limiting Audit Final Report written by the state for the Election Assistance Commission (eac.gov), who had provided grants to help with the process. We’ll be revisiting this Final Report a few times for both the math and practical considerations of actually conducting the audit.

Let’s start with the math. Much of the following information is taken from A Gentle Introduction to Risk-limiting Audits and Risk-Limiting Post-Election Audits: Why and How, both authored by, among other people, the Mark Lindeman quoted above, and the seminal Evidence-Based Elections by Stark and Wagner. Helpfully, Stark was part of the process in Arapahoe County’s pilot. Let’s dive in.

The easier type of risk-limiting audit is called ballot polling. I’ll give a simple example to show how straightforward this method is in practice and the really surprising (in a good way) ramifications of how the math works out. The procedure outlined below can be adapted for elections requiring a super majority, or where the winner doesn’t necessarily have the majority of the vote. But taking a simple case where the winner has over 50% of the votes, here’s how Ballot Polling would work. (Direct quotes are all from Gentle Introduction, and are indicated by indented text in the following examples)

Ballot Polling Procedure:

1) Let s be the winner’s share of the valid votes according to the vote tabulation system; this procedure requires s > 50%. Let t be a positive “tolerance” small enough that when t is subtracted from the winner’s vote share s, the difference is still greater than 50%. (Increasing t reduces the chance of a full hand count if the voting system outcome is correct, but increases the expected number of ballots to be counted during the audit.) T will be our running test value, and we’ll start by setting T = 1.

2) Select a ballot at random from the ballots cast in the contest. A ballot can be selected more than once; the following steps apply each time.

3) If the ballot does not show a valid vote, return to step 2.

4) If the ballot shows a valid vote for the winner, multiply T by (s−t)/50%.

5) If the ballot shows a valid vote for anyone else, multiply T by (1−(s−t))/50%.

6) If T > 9.9, the audit has provided strong evidence that the reported outcome is correct: Stop.

7) If T < 0.011, perform a full hand count to determine who won. Otherwise, return to step 2.

Pretty simple. Pick a random ballot and look at it with human eyes; if it confirms the winner we get closer to thinking the winner won and we increase our T, if it disputes the winner we feel a little pang of doubt and we decrease our T because maybe we are wrong about the winner. Once our T is big enough, we’re convinced. If T bottoms out, or if T never gets big enough to convince us, we end up reviewing all the votes. The equation takes into account the winner’s margin, so we will most likely check fewer ballots in a landslide and more ballots in a close race. Makes sense, right? Let’s work through an example to cement our understanding.

Ballot Polling Example:

Suppose one candidate reportedly received share s = 60% of the valid votes. Set tolerance t = 1%. If the reported winner really received at least s−t = 59% of the vote, there is at most a 1% chance that the procedure will lead to a (pointless) full hand count. Note that 1−(s−t) = 1−59% = 41%. To audit, we repeat steps 2–7, drawing ballots at random and updating T until either T > 9.9 or T < 0.011. The number of ballots eventually audited depends on the vote shares and on which ballots happen to be selected. If the first 14 ballots drawn all show votes for the winner, T = (59%/50%)×(59%/50%)×··· ×(59%/50%) = (59%/50%) 14 = 10.15, and the audit stops.

Of course the winner only won 60% of the votes so we’ll almost certainly draw some not-winner ballots here and there and wind up reviewing more than 14 total ballots. But as it turns out, not as many more as you might think. I made this quick google doc you can play with to change the share, tolerance, and order of votes polled to see how many ballots it takes for T to go over 9.9. (Please put it back like you found it more or less, when you are done experimenting). This is the google doc chart of somewhat realistic ballot pulls, with ballot 85 putting us over.

The really astonishing way the math works out:

When the outcome is correct, the number of ballots the audit examines depends only weakly on the number of ballots cast, so the percentage of ballots examined in large contests can be quite small. For example, in the 2008 presidential election, 13.7 million ballots were cast in California; Barack Obama was reported to have received 61.1% of the vote. A ballot polling audit could confirm that Obama won California at 10% risk (with t = 1%) by auditing roughly 97 ballots—seven ten thousandths of one percent of the ballots cast—if Obama really received over 61% of the votes

Comparison Audit Requirements

Another type of risk-limiting audit, a Comparison Audit, is even more impressive in the small number of ballots required to be checked. However, a comparison audit requires you to be able to compare how a specific ballot was tabulated to what that specific ballot actually says. That requires keeping ballots organized so that you can select a ballot at random (say, precinct 23, batch 50, ballot 7), see how it was tabulated, and then actually go find the ballot and have a human double check what it actually says. This matching up is clearly more of a logistical challenge than you have with ballot polling, where you just need to be able to find the next random ballot.

For a comparison audit, you compare the tabulated results to a fresh human review of the ballot. If the previous result and the human re-check agree, great. If the previous result was not recorded for the winner but should have been, that’s considered an “understatement” and wouldn’t affect the outcome because it favors the winner. If the recorded result was for the winner but shouldn’t have been, that’s considered an “overstatement” and improperly helped the winner by one vote. If the vote was recorded for the winner but should have been recorded for the loser, that’s a two vote swing. One vote overstatements or understatements can be from light marks, stray marks, hanging chads, etc, and certainly can and do happen. Two vote overstatements or understatements should be quite rare as they require two errors of interpretation from the same ballot. Quotes are again from the Gentle Introduction and are indented below. The equations are written for a risk level of 10%.

Comparison Audit Procedure

The “diluted margin” m is the smallest reported margin (in votes), divided by the number of ballots cast. Suppose the audit has inspected n ballots. Let u1 and o1 be the number of 1-vote understatements and overstatements among those n ballots, respectively; similarly, let u2 and o2 be the number of 2-vote understatements and overstatements. The audit can stop when n ≥ (4.8+1.4(o1 +5o2 −0.6u1 −4.4u2))/m

You can compare ballots one by one, or as a practical consideration, you can take a guess at n based on your anticipated error rate, and process them in stages, reviewing a set of ballots in parallel.

Comparison Audit Example

Suppose that 10,000 ballots were cast in a particular contest. According to the vote tabulation system, the reported winner received 4,000 votes and the runner-up received 3,500 votes. Then the diluted margin is m = (4000−3500)/10000 = 5%. The auditor draws a ballot at random and checks by hand whether the voting system interpretation of that ballot is right before drawing the next ballot. If there is one 1-vote understatement and no other misstatements among the first 80 ballots examined, u1 = 1 and o1, u2, and o2 are all zero and the audit can stop, because 80 ≥ (4.8−1.4×0.6×1)/ 5% .

The even more astonishing way the math works out for a comparison audit:

As you can see when there is a wide margin auditing just a small number of ballots is enough. Even for a narrow race with buggy results, it doesn’t take that many ballots to be sure you’ve identified the correct winner of a race. From our Obama in California example where ballot polling needed to check around 97 ballots, here depending on error rate, we would be expecting to check maybe 50 or 60. Out of 13.7 million!

Colorado Legislation

Originally made law in 2009 by Colorado’s 2009 bill, HB1335, Concerning Requirements for Voting Equipment

(1) (a) The general assembly hereby finds, determines, and declares that the auditing of election results is necessary to ensure effective election administration and public confidence in the election process. Further, risk-limiting audits provide a more effective manner of conducting audits than traditional audit methods in that risk-limiting audit methods typically require only limited resources for election races with wide margins of victory while investing greater resources in close races.”

(b) By enacting this section, the general assembly intends that the state move toward an audit process that is developed with the assistance of statistical experts and that relies upon risk-limiting audits making use of best practices for conducting such audits.

(2) (a) Commencing with the 2014 general election and following each primary, general, coordinated, or congressional vacancy election held thereafter, each county shall make use of a risk-limiting audit in accordance with the requirements of this section. Races to be audited shall be selected in accordance with procedures established by the secretary of state, and all contested races are eligible for such selection.

and later modified in 2013 by HB1303 to move the deadline to 2017 (see section 77) or see the Colorado Revised Statutes 1-7-515 (2017) (Page 234).

Up until now, the existing audit protocol was a random selection audit of 5% of the ballots, but with no mechanism for overturning an incorrect result. But now, now we will have transparent auditing to know our election results reflect the genuine will of the people based on votes cast. Ok, yes I know, auditing doesn’t address in-person voter fraud, which is thankfully rare, or improper influence on voters, or people being turned away because they don’t have ID, or all the other things that impact who gets to vote and what vote they cast. But it does check that the results of the election truly reflects the ballots cast, correcting random machine error, human error, or malicious altering of the results via hacking or other means; that’s pretty reassuring.

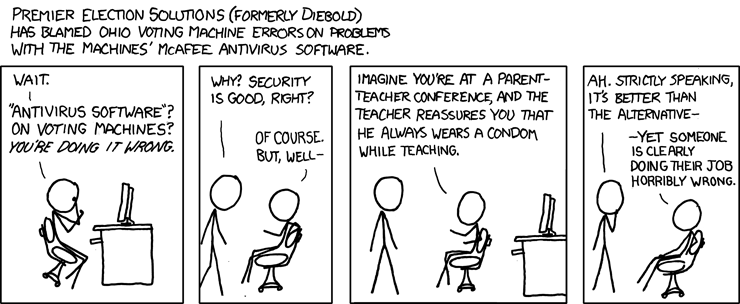

Requite XKCD since this is an awfully nerdy post

Risk Limiting-Audits In Real Life — Colorado’s Implementation

After the legislation was passed the Secretary of State swung into action. Since both ballot polling and comparison audits require a ballot to check against, the first challenge was making sure all counties had equipment that involves or creates a paper record (cast vote record — CVR) that can later be checked. Details of the pros and cons of the equipment evaluated are in the Final Report which I’ll be referencing and pillaging for photos throughout this section.

Another challenge that came up was transparency and if the public would be able to witness the recount and inspect the audited ballots themselves, which required legislation to be passed clarifying the situation. In 2012 the Colorado legislature passed HB 1036 to say yes to transparency. The bill says both “An interested party may inspect and request copies of ballots in connection with such recount without having to obtain a court order granting such inspection” and “an interested party may witness the handling of ballots involved in the recount to verify that the recount is being conducted in a fair, impartial, and uniform manner so as to determine that all ballots that have been cast are accurately interpreted and counted; except that an interested party is not permitted to handle the original ballots.” Provisions are made to ensure the privacy of voters. According to our friends at the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, this process got off to a rough start. Hopefully, practice and technology will continuously improve the transparency of the audits (see the end of this post for a little more about transparency).

Apparently subscribing to the Go Big or Go Home approach to auditing, Arapahoe County chose to do a comparison audit, meaning they needed to get organized enough to find and inspect any specific ballot randomly selected to be reviewed and match it to how that ballot was tabulated and reported by the machine. And get organized they did! According to the final report, a total of 146 batches consisting of 139,821 ballots were scanned and stored in boxes in numerical order in the Arapahoe County ElectionsWarehouse, as shown in the photographs below.

Once the election was over, the initial results tabulated, and the ballots organized, it was time to start randomly picking ballots. Based on the parameters of the election and the diluted margin of the reported results, in the end 44 ballots were to be randomly selected to be checked. Random numbers are notoriously hard to come by, but rolling dice in front of witnesses is a nice option; an exciting action shot of these rolls are featured in the (now unavailable) video. Luckily the Final Report captures some pictures for posterity.

Even with all the organization, the description in the Final Report of two ballots in batches that got out of order was just heartbreaking. Colorado officials and boffins have started working on a new technology system involving imprints to short-circuit much of this effort in the future. In the end, all of the selected ballots were found and checked and the audit was deemed a success.

“One of the things that was awesome about the process here in Colorado — you had counties working on it, you had a great investment in time from the Colorado Secretary of State’s office, and then we had a group of election activists and stakeholders who came together with the express purpose to make the election process better. It’s people who, if we were to go out for a beer, we probably wouldn’t agree on many things. But everybody came together because we wanted to make the process better, we wanted to make it more transparent, and we wanted the public to have greater confidence in what we do. I think that’s one of the most rewarding things about what we’ve done in Colorado is that collaboration. It’s really cool when people can come together with the same mindset and get something done.” –Matt Crane, Arapahoe County Clerk

Kudos, Mr. Crane, on a job well done.

Risk-Limiting Audits — What Happens Next

As you can tell from the videos and articles cited in this post, there is lots of interest around the country, and even the world, to see how the process works out in Colorado. Several other jurisdictions are considering legislation to require risk-limiting audits in particular. Take a look at all legislation introduced from 2013 to date:

Washington’s HB2406 puts it nicely ” It is the intent of the legislature to ensure our elections have the utmost confidence of the citizens of the state.” The bill adds an option of both ballot polling and comparison risk-limiting audits as an alternative to a 4% annual recount. The bill passed and was approved by the Governor on March 22, 2018.

Rhode Island tried to pass a bill for years and finally got S0413 through in 2017 stating “The general assembly hereby finds, determines, and declares that auditing of election results is necessary to ensure effective election administration and public confidence in the election results. Further, risk-limiting audits provide a more effective manner of conducting audits than traditional audit methods in that risk-limiting audit methods typically require only limited resources for election contests with wide margins of victory while investing greater resources in close contests.” They intend to start in 2020.

Virginia took an interesting approach in SB1254 randomly selecting jurisdictions to use a risk-limiting audit, making sure every jurisdiction is audited at least every five years. This bill was approved by the governor and goes into effect July 1, 2018. I tried but couldn’t find any information on how the implementation of this plan is going so far.

California is currently considering AB2125 which seeks to replace their current mandated 1% manual tally with a ballot-level comparison audit by 2022. The bill passed out of the Assembly unanimously but hasn’t had a vote in the Senate yet, and the California session is nearly over. Illinois, Ohio, New Jersey, and New York are still considering their bills. Wisconsin’s AB743 Post-election risk-limiting audits didn’t make it out of the Campaigns and Election committee this year and Georgia hasn’t been able to pass anything yet either but did have some bills trying to move in that direction this year.

Finally, Congress is considering two bills looking to provide grants for implementing risk-limiting audits.

Additional Resources and Rabbit Holes

I’m a big fan (and patron) of Numberphile, and was excited to discover they took a helpful look at one other potential method you could use for a risk-limited audit, and explains how you can keep checking additional ballots until you reach the desired level of certainty. “Professor Ron Rivest discusses a technique for post-election audits – taking small samples and using Pólya’s Urn.”

Risk-limiting audits rely on transparency, so the software used for the ballot selection and various calculations chosen was all open source. Here are some resources about the software if you are interested:

http://freeandfair.us/blog/risk-limiting-audits/

https://github.com/FreeAndFair/ColoradoRLA

NCSL slides from a presentation in 2015 about Risk-Limiting Audits in Colorado

Arapahoe County Clerk video on Implementing Risk-Limiting Audit (with Matt Crane)

Boulder County Clerk video on The History of Risk-Limiting Audit (with Hillary Hall)

Initially, Boulder County saw the audit as a way to make sure the machines were doing a good job and they feel like the audit has helped them improve the entire process including educating the public on best voting practices as well as helping the public gain confidence in our democracy. She encourages all other county clerks around the country to adopt risk-limiting audits if at all possible.

(Lengthy) EAC Public Forum on Election Security video

Embedded (now missing) video that sparked this whole journey for me (in case it comes back):

For another fun election-related rabbit hole, read up on ranked choice voting and its June 12 debut in Maine which voters voted to keep in their referendum on June 12, 2018, overturning a special session bill delaying implementation and also disagreeing with their Governor (like on so many other things) who says he won’t certify the ranked choice primary results calling it “the most horrific thing in the world”. This whole story is truly nuts. But the math for ranked choice voting is pretty interesting, you should check it out sometime.

About BillTrack50 – BillTrack50 offers free tools for citizens to easily research legislators and bills across all 50 states and Congress. BillTrack50 also offers professional tools to help organizations with ongoing legislative and regulatory tracking, as well as easy ways to share information both internally and with the public.